Nowadays, it seems like every month is Dry January. In the Netherlands, alcohol consumption has been declining for years, to the alarm of brewers and beverage sellers. Can the growing popularity of alcohol-free drinks make up for that decline?

Alcohol-free wine? Italy scoffed at the idea for years. Since 2021, wine that has been dealcoholized—wine from which the alcohol has been removed—has officially been recognized as “wine” in the European Union. In all member states except Italy, that is, where the government wanted nothing to do with it.

Until the country made an unexpected U-turn last week. After years of resistance, the production of dealcoholized wine was finally approved at the end of December by the Ministries of Agriculture and Finance. Much to the delight of wine producers, who are eager to get started.

Whether intentional or not, the timing was ideal—right before Dry January. Worldwide, a growing number of people are taking part in the initiative to abstain from alcohol in January. IkPas, an organization that supports people in doing so, reports that 1.2 million Dutch people are skipping alcohol this month. The perfect moment to switch to a “zero-zero.”

0.0 beer growing ever more popular

Alcohol-free drinks are on the rise. 0.0 beer in particular is popular: about one in six adult Dutch people (16.7 percent) drink alcohol-free beer every month (Trimbos Institute, 2024), compared with roughly one in ten (9.8 percent) in 2018. Alcohol-free wine and cider are significantly less popular, with a market share of under 2 percent—but who knows, Italian wine producers may change that in the future.

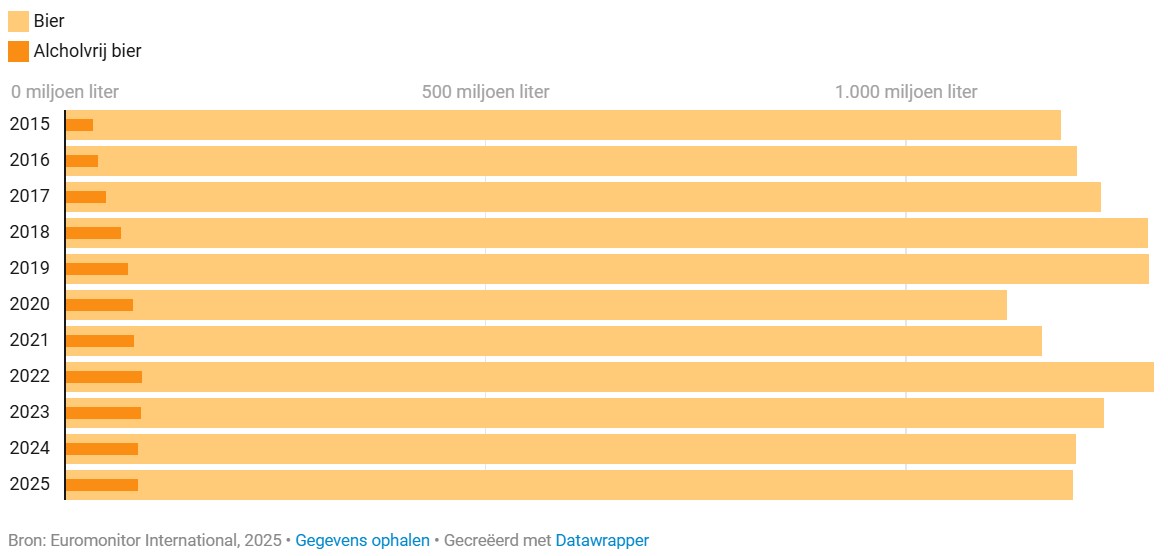

In the Netherlands, alcohol-free beer now accounts for 7.2 percent of total volume (Euromonitor International, 2025). Ten years ago, that figure was just 2.8 percent.

According to François Sonneville, beverage sector analyst at Rabobank, several factors are at play. “First of all, during the COVID-19 crisis consumers became more aware of the health benefits of not drinking. Especially in the aftermath of the pandemic, the share suddenly rose sharply. In addition, the range of products has improved enormously in recent years.”

Share of alcohol-free beer in total beer sales

Volume in million liters. In the Netherlands, alcohol-free beer accounted for 7.2 percent of total sales volume in 2025. Ten years earlier, that figure was just 2.8 percent.

The watery, sweet, and sometimes even musty character that used to define alcohol-free beers is a thing of the past, according to the analyst. “Nowadays, a Heineken 0.0 tastes roughly the same as a ‘regular’ pilsner.”

“The difference is no longer detectable,” agrees Frederik Kampman, founder and CEO of Amsterdam-based craft beer brand Lowlander. “Not in terms of taste, and not sensorially. The mouthfeel is the same.”

Even if true purists claim otherwise. He laughs. “For fun, we had people do blind tastings at the Tapt beer festival. They confidently say they can definitely pick out the 0.0 beers, and in the end you see that they actually can’t. I think that’s a great confirmation. Alcohol-free is no longer a compromise.”

Jokes about Buckler

Besides the range of products, the image has improved considerably. According to Sonneville, the days when Youp van ’t Hek could bring down an alcohol-free beer brand with a single well-aimed joke—RIP Buckler—are definitively over. The advantages are simply too clear: “At the pub, people no longer have to choose between an evening of fun and showing up fresh at work or at the breakfast table the next morning.”

In Europe, the Netherlands is in fact a mid-range performer. In front-runner Spain, the share of non-alcoholic beer in total beer volume already exceeds 15 percent. According to Sonneville, this is linked to the increase in excise duty on soft drinks and other non-alcoholic beverages as of January 1, 2024. “That has put the brakes on growth. I understand that the government wants a level playing field, but if you want to promote alternatives to alcohol, this may not be the best solution.”

The Dutch Brewers’ Association is therefore calling for an exemption for alcohol-free beer. The United Kingdom already has such an exemption.

Shrinking pilsner market

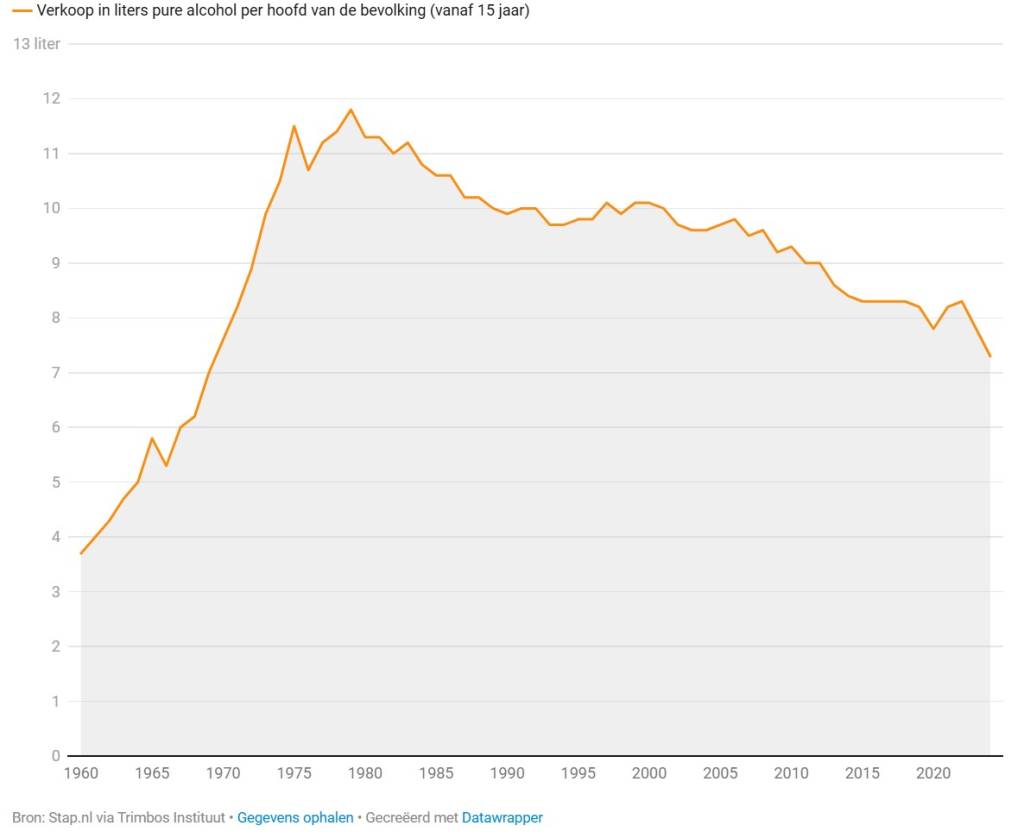

The rise of 0.0 is linked to another development. Dutch people are drinking less and less alcohol, according to data from the Trimbos Institute. Between 2000 and 2024, alcohol consumption in the Netherlands fell from 10.1 liters to 7.3 liters of pure alcohol per capita (–27.7 percent).

Especially in the past two years, a sharp downward bend is visible. According to Sonneville, this is partly related to the war in Ukraine and the energy crisis and high inflation that resulted from it.

Dutch people are drinking less and less alcohol

Alcohol consumption peaked in the late 1970s and has been declining ever since.

Brewers are feeling the effects. Grolsch saw volumes in its home market fall by 4.5 percent in 2024 and revenue decline by 1.3 percent, according to its most recent annual report. In addition to inflation and rising costs, the Twente-based brewer attributes the drop to waning consumer interest. “The appeal of beer, mainly pilsner, is under pressure (…). The growth of alcohol-free beer is not able to offset the decline in pilsner.” Grolsch additionally reports that the share of alcohol-free and low-alcohol beer in total beer revenue was around 12 percent in 2025. That share is increasing every year by “a few percentage points.”

Heineken also saw revenue in its home market fall by a “low single-digit percentage” in the first half of 2025, and volume by a “high single-digit percentage,” the FD reports.

Despite this, the brewer struck an optimistic tone in a response. “In the Netherlands, we are seeing a declining pilsner market,” spokesperson Derk de Vos acknowledges. “But we do see growth in certain segments, such as 0.0. Whereas in 2017—the year Heineken 0.0 was introduced—only one in twenty beers sold in supermarkets was alcohol-free, by 2025 that figure is already one in ten.”

Structural decline

Nienke van de Streek, CEO of the country’s largest liquor store chain Gall & Gall, also appears unconcerned. “We do not see this development as a contraction, but as a clear shift in consumer behavior. It is precisely these kinds of movements that create wonderful opportunities for innovation,” she said in a written response.

According to Van de Streek, the share of no- and low-alcohol products in total revenue is still “relatively small,” without citing percentages. “But the growth curve is strong. That is what really tells the story.”

Sonneville expects the alcohol and pilsner market to continue shrinking. In addition to the focus on health, the digitalization of society plays a role. “Alcohol no longer has the same social bonding function it once did. With more people working from home, there are fewer office drinks. Young people see and talk to their friends more online and less in the pub. In recent years, we have seen a structural decline of 1 to 2 percent annually. I expect that trend to continue over the next 15 years.”

Switching to no & low

For Lowlander CEO Kampman, developments in the sector were reason enough to change course at the beginning of 2025. From now on, the beer brand is focusing exclusively on alcohol-free (0.0 to 0.5%) and low-alcohol (0.5% to 3.5%) beers—no & low, in industry jargon. Not entirely coincidentally, the company announced this move during Dry January.

When he founded the company ten years ago, the entrepreneur drew inspiration from the botanicals—herbs, spices, and fruits—that give gin its flavor. Couldn’t he brew beer with those? It soon became clear that Lowlander’s beers, thanks to those herbal additions, needed much less alcohol to be flavorful.

An unexpected stroke of luck, as it meant Kampman suddenly had something perfectly aligned with current market demand.

OMake up for it — or lose revenue

The shift was therefore less radical than it might seem, he explains. “Even before the change, 60 to 70 percent of our revenue already came from alcohol-free and low-alcohol beer.” Which also means that 30 to 40 percent did not. “Of course, it was a risk to let that go. But we believed in it. In the United States and the United Kingdom, there are already dedicated no & low brewers; in the Netherlands, there weren’t yet. We saw an opportunity to claim that position.”

A year later, revenue is “comparable” to the €7 million Lowlander generated in 2024, says Kampman. “But the mix is completely different. Ninety percent of volume is now no & low. With our retail partners, we have already fully replaced the alcoholic beers with alcohol-free and low-alcohol alternatives, and in the hospitality sector we are well on our way. Hospitality operators also see that guests are drinking less alcohol, and retailers notice that customers are buying less of it. If you can’t compensate for that, you lose revenue.”

At Gall & Gall, the range has expanded significantly in recent years, CEO Van de Streek confirms. “Where the offering used to consist mainly of one-to-one alcohol-free substitutes, a much richer landscape has now emerged. That’s why we’re investing not only in no- and low-alcohol products, but also, for example, in mocktails and sparkling teas.”

Diversification is the key word

Rabobank analyst Sonneville also does not believe that beverage producers and retailers can offset the decline with alcohol-free and low-alcohol alternatives alone. “It’s a valuable addition, but not a complete solution.”

After all, people who choose not to drink alcohol have plenty of options. Soft drinks, of course—though you don’t want to spend an entire evening in a restaurant or bar drinking cola. But trendy (fermented) beverages such as kombucha and ginger beer, as well as “health drinks”—sugar-free energy drinks or so-called prebiotic sodas with added fiber—are also on the rise.

In a rapidly changing market, diversification is the key, according to the analyst. “Producers need to look at a broader portfolio. The days when a brewer only sold beer are over.” That realization already seems to have sunk in. In 2025, Heineken took a minority stake in Amsterdam-based beverage brand Stëlz, which makes hard seltzer—sparkling water with a fruity flavor and alcohol—popular in part because it contains far fewer calories than beer or wine.

That same year, the group opened a brand-new R&D center in Zoeterwoude. There, teams are working on the next generations of 0.0 beer, without alcohol and without calories, and on fermented soft drinks with “certain health benefits.” During a visit to the new wonder lab, the brewer was not yet willing to say much more about it.

Another example: in the summer of 2024, Carlsberg put €4.8 billion on the table for the fruit juices, syrups, and soft drinks of British company Britvic. Brewers are becoming all-beverage companies, Sonneville observes. “The pond they’re fishing in is getting smaller, so they need to adapt their strategy.”

Source : https://mtsprout.nl/groei/businessmodellen/dry-january-alcoholconsumptie-alcoholvrij